It’s hard not to feel at least a bit of trepidation about what the near future could hold for space exploration, given a tense political climate and never-ending global conflicts, so what about the very long-term future?

A conversation with Victoria DeFazio*, Co-Lead for the Cosmic Futures Project (SGAC’s Space Safety and Sustainability Project Group)

In the wake of recent geopolitical events, relations of mutual trust and cooperation between actors seem to be faltering. In a climate of mistrust, isolationism and retaliatory dynamics, initiatives aimed at the future safety of humanity are left behind and struggle to flourish. For this reason, it appears as a moral duty to ensure that the voices of young generations are heard, problems are brought to light and cooperation is kept alive.

With the objective of bridging initiatives aligned to the Space Law and Policy Project Group’s vision and mission, we joined in a conversation with Victoria DeFazio to learn more about the project she co-leads: the Cosmic Futures project, under the SGAC’s Space Safety and Sustainability Project Group.

Victoria, could you introduce us to the project and the idea behind it?

Cosmic Futures is a project within the SGAC Space Safety and Sustainability Project Group that aims to influence policy that could affect humans in space, not just in the next few decades, but in the next thousands of years. With such a huge scope, how can a project produce meaningful and poignant results that can be implemented into policy written today? This is what we aim to find out.

The project was started by Jordan Stone. Jordan is an astrobiologist and an active SGAC member, being part, among other projects, of the SLP Armed Conflicts in Outer Space Research Group, co-led by Sima Moradinasab and Daniel Duchaine.

Looking up into the night sky and wondering where humans will be hundreds – and even thousands – of years from now is a universal experience. It’s hard not to feel at least a bit of trepidation about what the near future could hold for space exploration, given a tense political climate and never-ending global conflicts, so what about the very long-term future? It’s not always easy to have faith that government leaders and policymakers will have the best interests of humanity in mind when crafting space policy. This is why the project was launched in the first place.

Once the idea triggered the creation of the project, which were the next steps that were taken?

The first step was to anticipate the impact of humanity’s activities in space in the long-term future. Jordan and other members of our amazing interdisciplinary team wrote project briefs on numerous different topics related to humans in space that interested them. These project briefs included preliminary research on diverse topics, such as excessive asteroid mining, bringing animals to space, mining on the Moon, mental health in space, cultural heritage preservation, and many, many more. All of these themes are worthy of a full exploration and analysis, but, of course, we had to find a way to scale down our scope. We needed to hone in on three “flagship projects.”

The projects we chose to spearhead needed to be representative of the concerns of our whole team, especially since our team is concerned with representing people of all backgrounds and in all nations in space policy. But our work is not only a study in the humanities, it is also a highly analytical research project. Thus, our process for choosing flagship projects needed to be both democratic and quantitative.

To determine the flagship projects, members of our priority projects subteam read through the briefs and gave them a numerical ranking on the basis of four factors. These factors included: the potential impact of each topic on the future of humanity, the likelihood of each topic to occur, how neglected the topic currently is in the space ecosystem, and how feasible it would be to implement policy solutions to address the topic. These rankings were given by team members based on the research presented to them in the project briefs (with many topics in the briefs not having extensive literature already written) and were largely up to the judgement of the team members.

Was there also a need to discuss your ideas with people outside the group? Perhaps, to avoid tunnel vision or to raise a problem that had not been considered?

Just when we thought we had the necessary scores to pick our flagship projects, we consulted with an expert in the epistemology of influencing the long-term future, Jim Buhler. His insight helped us to ascertain that our scope was still largely undefined. Based on this discussion, we decided to narrow our focus into researching risk factors caused by humans in space with broad effects instead of trying to tackle specific scenarios with existential threats to humanity and many unknowns. Thus, we categorized our project briefs as either bad future scenarios or risk factors. Once we sorted out our risk factors, we picked three to be our priority projects.

Could you please outline the priority projects that were chosen?

The chosen topics were the ones that scored highest, meaning that they have a high potential impact on our future, they are very likely to occur, they are highly neglected in the space community, and a solution can be achieved easily (relatively speaking).

These encompass: (1) a lack of inclusivity in decision-making in space (primarily relating to non-space faring or non-Western nations), (2) unchecked, or rapid space expansion, and (3) unsafe use of AI in space.

What’s the way ahead for the Cosmic Futures Project?

The next phase of our project includes further researching the impacts of these risk factors so that we can develop potential policy solutions. We aim to determine the effects of these risks on the next 6,000 years of humanity in space. Our research will be guided by our working principles implementation team, who have further narrowed down our approach and scope within these projects.

An ambitious future requires bold projects, and while our project looks further ahead than ever before, we believe that our study will help shape policies that lay the groundwork for our descendants to live peacefully, sustainably, and equitably in space.

How could anyone interested in the project contribute to it?

If you would like to learn more and/or contribute to our project, you can reach out either to myself at [email protected], or to Jordan Stone at [email protected]

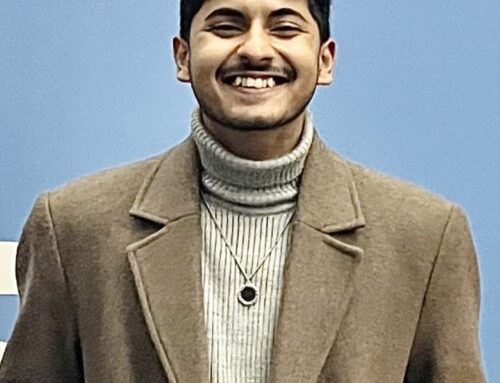

*Victoria DeFazio is a recent graduate of Arizona State University with a B.S. in Astrophysics. She is currently a Research Technician with Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera and Intuitive Machines in Phoenix, AZ. In her role there, she studies changes to the lunar surface and creates data products for lunar exploration. Victoria is a member of the Space Generation Advisory Council’s Space Safety and Sustainability-PG and the NCAC Policy Task Force. Additionally, she is a member of the Association for Women in Science Advocacy Task Force and Vice President of Events for the AZ chapter of the Space Force Association.