“The special environment of outer space, as a second home of humans, requires moving from lex generalis to lex specialis“

‘The legal system of outer space is today also closely linked with human rights’, Manfred Lachs (at p. 689).

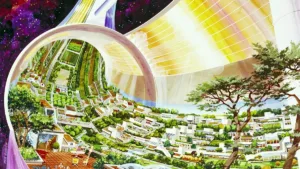

The world is changing rapidly. On the one side, humanity has seen global crises such as global warming, climate change, and the threat of nuclear war. On the other side, humans, by their very nature, are ambitiously seeking a new life, though not on Earth, but in outer space. Therefore, outer space is no longer regarded as a subject for science fiction writings and movies, but is becoming a potential place for human settlements.

The term ‘human settlements in outer space’, is defined as establishing a second permanent house in outer space by human beings (Aram Daniel Kerkonian, at p. 2). There is no doubt that settlements in outer space should be compatible with general principles of space law regime, notably Article II of the Outer Space Treaty (OST) which prohibits any claim of sovereignty over celestial bodies.

Among many issues raised by space settlements, respecting and protecting human rights represent one of the most significant concerns. The main question is whether lex lata (the law as it is) would be sufficient for respecting human rights in space settlements. If not, is it necessary to take specific steps to move from lex generalis (general law) to lex specialis (special law)?

Extraterrestrial Application of Human Rights

Legally, human rights rules are not limited to the Earth. They also extend to relations between international actors in other areas beyond national jurisdiction of States, including outer space. This is exactly what was expressed by Brownlie when he states ‘ There is no reason for believing that international law [including rules of human rights] is spatially restricted (James Crawford, at p. 726). Therefore, “it would seem counterintuitive to argue that the principles that are to guide the rights of humans on Earth would not also guide the rights of human in space” write Daniel Ireland-piper and Steven Freeland (at p. 110).

This assumption is also strengthened by the legal nature of the international legal system and space law’s place within it. International law is regarded as a unified legal order (Bruno Simma & Drik Pulkowski, at p. 17). This means that none of the current legal sub-systems in international law can fully derogate from general rules of international law (ILC, at. 37).

On this basis, interaction between different regimes, including space law and human rights law would be inevitable. Additionally, while the space law regime contains a set of specific primary and secondary rules, it is to be solely deemed as a special regime and not a self-contained regime. (Christopher D. Johnson, at pp. 154-155). It follows that where there is no lex specialis on space activities, lex generalis, including general rules of human rights will be applied.

Considering that, the question is not whether general rules on human rights can apply and extend to outer space. But the main concern is whether we need lex specialis for human settlements in outer space? If yes, then why?

The Need for Lex Specialis in Space Settlements

The codification and progressive development of space law regime and international human rights regime fall within the competences of two different UN organs: the five space law treaties, as part of the hard-core corpus juris spatialis were formulated within the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), and the International Bills of Human Rights, representing the main part of the human rights regime, were adopted within the UN General Assembly and before the adoption of the OST.

While the COPUOS is regarded as a subsidiary organ of the General Assembly, its main concern has always been to promote international cooperation in peaceful uses of outer space. Accordingly, the primary goal of international instruments on human rights is respecting and protecting the fundamental rights of human beings.

One may argue that there is no need for lex specialis since (i) the General Assembly and its subsidiary organ-i.e., the COPUOS can interact with each other; and (ii) human rights principles as part of general rules of international law, extend to outer space and human settlements in this new environment. This assumption, however, would break the logic of lex specialis principle, according to which special provisions are ‘more effective than those they are general’.(at p. 59).

There is no doubt that given the extraterritoriality of human rights rules, space settlers as well as those who live on the Earth, are entitled to all fundamental rights such as the right to life, the right to privacy, the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress, the right to health, etc. However, special characteristics of outer space require creating concrete rules for ensuring space settlers’ rights. For example, the precise meaning of ‘personal data’ as a component part of the right to privacy was neither mentioned in Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), nor in other international instruments. Additionally, while the human rights regime determined general requirements on limitation and derogation of human rights, evaluating these criteria such as proportionality, legitimation, and legality test- cannot be done without taking special features of outer space into account. One important question in this regard is whether space law permits the limitation of space settlers’ right to enjoy scientific progress on the basis of the national security of States. This concern is of crucial importance since in the context of space law, national security of States often has priority over other aspects of international cooperation in outer space. One clear example can be found in Article 19(3)(C) of the ISS Agreement, according to which a transfer of technical data and goods ‘need not be conducted if the receiving Partner State does not provide for the protection of the secrecy of patent applications containing information that is classified or otherwise held in secrecy for national security purposes’ (ISS Agreement, Article 19(3)(C)). Needless to say, these lacunae should be filled by lex specialis.

The need for special provisions in space settlements is not limited to primary rules, but extends to secondary rules. Certainly, the horrors of human rights violation by governmental and non-governmental sectors cannot be overlooked. This is where the secondary rules play a significant part. However, in the framework of space law treaties, there is no compulsory clause for submitting space-law disputes to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) or any other international tribunals. That said, the prediction of special provisions for both dispute settlement mechanisms and complaining procedures by space settlers seems necessary.

Another aspect of secondary rules relates to rules on responsibility in outer space. Due to the increasing number of space activities done by private sectors, it is possible that the rights of space settlers are violated by actors other than States. Article VI of the OST provides that private activities in outer space should be carried out under the authorization and supervision of States. For the purpose of this provision, authorization conditions are determined at the discretion of States (Michael Gerhard, in: Stephan Hobe, Bernhard Schmidt-Tedd et.al (eds.), Volume I, at pp. 415-416). While respecting fundamental rights of human settlers can be added as one of these conditions, resorting to general rule of interpretation as set forth in Article 31 of the VCLT, it appears that the sole intention of drafters was to authorize and supervise private space activities, not to bear international responsibility for human rights violation by these actors. This is the main reason why establishing lex specialis for responsibility of private sectors towards human settlers in outer space is crucial.

These considerations demonstrate that the special environment of outer space, as a second home of humans, requires moving from lex generalis to lex specialis. Without doubt, in any case, general rules of human rights will remain in the background and support the correct interpretation of special law governing outer space.

About the Author

This post was written by Sima Moradinasab on behalf of SLP’s space settlements team. Sima Moradinasab is a PhD candidate in Public International Law at Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran. With a keen interest in space law, she started researching and writing in this area since she was a master student. She is currently a visiting researcher in the International Institute of Air and Space Law (IIASL) of Leiden University where she is writing her PhD thesis. Sima is also a research member of the ‘Space Settlements’ research group of the SGAC Space Law and Policy (SLP) Project Group.