“The implementation of environmental law remains a challenge that can be overcome through the use of remote sensing data, an emerging vital tool for providing comprehensive and accurate environment information”

Marie-Claire Brujin on behalf of SLP’s remote sensing team

Introduction

As the environment continues to change and the sustainability of our planet is continually impacted, monitoring changes plays a critical role in identifying negative developments, which in turn can lead to necessary action. Remote sensing data from satellites offers a powerful tool for this purpose, aiding in environmental monitoring and enforcing laws aimed at protecting our planet. However, the practice of utilising such data in legal proceedings varies across Europe, with technical and legal challenges hindering its use.

The Evolution of Environmental Law and Remote Sensing

Environmental law has developed rapidly at both international and European level since the 1970s, with thousands of sources regulating aspects of environmental protection. However, the implementation of environmental law remains a challenge that can be overcome through the use of remote sensing data, an emerging vital tool for providing comprehensive and accurate environment information.

Remote sensing involves the collection of data from satellite images, which can be used to monitor changes in land-use, deforestation, pollution, and other environmental indicators. The utilisation of remote sensing data is endorsed by international legal frameworks, including the United Nations Resolution 41/65 of 1986 which established principles of cooperation and access to satellite data, particularly in the context of natural disasters[1].

The Use of Remote Sensing Data in Environmental Enforcement and Court Proceedings

Remote sensing data plays a crucial role in environmental monitoring and policy enforcement across Europe. Environmental crimes, such as air and water pollution, hazardous waste offences, pesticide misuse, and wildlife crimes, are addressed through various initiatives at the European level, focused on identifying, investigating, and prosecuting offenders[2]. One of the earliest applications of remote sensing data in environmental litigation was the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, where Landsat – a US-based programme – provided critical information[3]. Sentinel, a European programme which is part of the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Copernicus initiative, has since been instrumental in monitoring natural disasters such as floods, deforestation, and earthquakes, contributing to environmental protection worldwide[4]. The European Union (EU) has further developed its competence in remote sensing, supported by programmes like Copernicus and Galileo and policies like the INSPIRE Directive, which aims to establish a comprehensive spatial data infrastructure across the EU[5]. Today, several EU programmes provide data to users on a fully open and free basis, supplying critical data for tracking changes in land use, deforestation and biodiversity[6]. In the agricultural sector, remote sensing is used to monitor farm subsidies, ensuring compliance with environmental conditions and, in the case of fisheries, to control and enforce community legislation[7].

In Member States of the EU, the use of remote sensing data in legal proceedings has been surprisingly common for a number of years. In the majority of published cases, however, it is only mentioned in passing. In most of the cases in which the courts cite the source of the remote sensing data, the data is taken from Google Earth or Google Maps[8]. One reason is that the data provided on these platforms is free of charge and accessible to everyone[9].

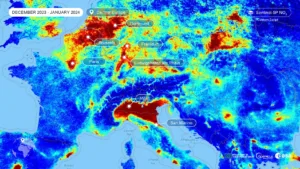

So far, satellite imagery and other remote sensing data have been successfully used in several court cases to establish facts that would otherwise be difficult to prove. For instance, in a case involving an illegal landfill site in the United Kingdom, archived satellite images provided critical evidence that showed the landfill’s operation over a period that extended beyond what was initially presented during the prosecution[10]. Another notable example includes a case involving an air quality plan in Germany where the court used satellite images to verify the possibility of air pollution from nitrogen dioxide[11]. This helped to assess the necessity of driving bans. Remote sensing data has also been instrumental in several other cases, such as determining the size of certain land areas[12] and animal habitats[13], identifying crime scenes[14] and the movement of land surface[15].

Many times, if the court does not already doubt the legitimacy or correctness of remote sensing data, the opposing party will challenge the satellite data’s validity. For this reason, courts often leverage an expert opinion[16].

Remote Sensing in the EU and Challenges

Despite these advances, there are still a number of legal and technical obstacles preventing the widespread use of remote sensing data in enforcing environmental laws enforcement. Technical issues involve data calibration and chain of custody, critical to maintaining the integrity of satellite data used in court. Legal obstacles include privacy concerns, intellectual property issues, and restrictions related to national security that can limit access to and the use of satellite data[17]. For these and further reasons, such as a lack of understanding of satellite technology and/or concerns about the timeliness, accuracy and confidentiality of the data[18], there is a certain reluctance among the EU Member States’ legal bodies to accept satellite data as court evidence. While the use of satellite data to resolve environmental disputes is more common in the Netherlands, other European countries are more wary of using it. An example of a case in which satellite images were dismissed as evidence includes the Judgement of 16.11.2005 of the Administrative Court Minden in Germany[19]. Satellite images that could have provided information on the size of certain land areas were rejected as evidence because they were deemed inaccurate due to the presence of a defect in the satellite technology.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Despite its potential to contribute to the sustainability of Earth, the application of remote sensing data in legal settings faces significant technical and legal challenges. To maximise the impact of remote sensing data in environmental protection, it is essential to address and overcome the challenges currently limiting its use. This includes establishing a baseline set of requirements for data quality, improving legal cooperation, and increasing awareness among legal professionals about the capabilities of remote sensing technology. By doing so, Europe can strengthen its commitment to sustainable development and environmental protection, ensuring that future generations inherit a healthier planet.

About the Author

Marie-Claire de Bruijn is a law student at the University of Cologne, Germany. She holds a university entrance diploma in business administration after five years of specialised studies. After working at the law firm BHO Legal, Cologne, and contributing to the industry through research projects, volunteering and currently as a mentor at Women in Aerospace-Europe, she is now part of the Remote Sensing Research Team of the SGAC Space Law & Policy Group.

Sources

[1] United Nations General Assembly (1986) Principles relating to remote sensing of the Earth from outer space (Resolution 41/65), retrieved from https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/oosadoc/data/resolutions/1986/general_assembly_41st_session/res_4165.html.

[2] Dighe, K., Mikolop, T., Mushal, R. W., & O’Connell, D. (2012) The use of satellite imagery in environmental crimes prosecutions in the United States: A developing area. In R. Purdy & D. Leung (Eds.), Evidence from Earth observation satellites: Emerging legal issues (pp. 65-70), Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

[3] U.S. Geological Survey, Landsat Chernobyl, retrieved from https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/landsat-chernobyl.

[4] Nagler, T., Rott, H., Hetzenecker, M., Wuite, J., & Potin, P. (2015) The Sentinel-1 mission: New opportunities for ice sheet observations. Remote Sensing, 7(7), 9371-9389, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs70709371; European Space Agency, The Sentinel missions, retrieved from https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Copernicus/The_Sentinel_missions.

[5] European Parliament and Council (2007) Directive 2007/2/EC establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE), Official Journal of the European Union, L 108, 1-14.

[6] Purdy, R., Leung, D., & others (2010) Using Earth observation technologies for better regulatory compliance and enforcement of environmental laws; European Commission, About Copernicus. Retrieved from https://www.copernicus.eu/en/about-copernicus; also European Global Navigation Satellite Systems Agency, Galileo Open Service Retrieved from https://www.gsc-europa.eu/galileo/service.

[7] Ibid.

[8] See for instance Tribunal of Brindisi (2022, February 15) Caliandro case; VG Schleswig (Administrative Court Schleswig, 2nd Chamber) (2020, December 10) 2 B 50/20 (Decision); VG Hannover (Administrative Court Hannover, 12th Chamber) (2023, February 9) 12 B 4795/22 (Decision); OLG Koblenz (Higher Regional Court Koblenz, 1st Criminal Senate) (2021, February 24) 1 StE 3/21 (Decision); Bundesverwaltungsgericht (Federal Administrative Court) (2008, December 2) BVerwG 4 BN 14.08 (Decision).

[9] As stated in OLG Düsseldorf (Higher Regional Court Düsseldorf) (2021, January 5) 2 RBs 191/20 (Decision).

[10] Purdy supra note 6.

[11] VG Gelsenkirchen (Administrative Court Gelsenkirchen, 8th Chamber) (2018, November 15) 8 K 5068/15 (Decision).

[12] Such as in VG Minden (Administrative Court Minden, 3rd Chamber) (2005, November 16) 3 K 2986/03 (Decision), reported in AUR, 2006, 433-437.

[13] Such as in VWGH (Administrative Court of Austria) (2014, November 27) 2012/03/0082: L65003 Hunting Wild Lower Austria.

[14] See e.g. Neuruppin Regional Court (2010, July 3) 11 Ks 321 Js 2/09 (Decision).

[15] Miazzi, L. (2002, June 7) Judgement in the Rovigo case, see London Institute of Space Policy and Law (2012) Evidence from space (pp. 31 f.), retrieved from https://www.space-institute.org/app/uploads/1342722048_Evidence_from_Space_25_June_2012_-_No_Cover_zip.pdf.

[16] VG Regensburg (Administrative Court Regensburg) (1996, April 25) RO 7 K 94.1846 (Final Decision) (unpublished).

[17] See also Williamson, R. A. (2000) The Landsat legacy: Remote sensing policy and the development of commercial remote sensing, Space Policy, 16(4), 233-244, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0265-9646(00)00051-3; also Court of Cassation (2017) Sentence n° 13822/2017: Point 4.1. and BVerfG (Federal Constitutional Court of Germany) (2006, May 2) 1 BvR 507/01. NJW, 2006, 2836-2837.

[18] See also VG Sigmaringen (Administrative Court Sigmaringen, 5th Chamber) (2020, March 27) 5 K 3036/19 (Decision); VG Minden, supra note 12; also explored in London Institute of Space Policy and Law, Evidence from space, supra note 15, pp. 332.

[19] VG Minden, supra note 12.